![astrology]()

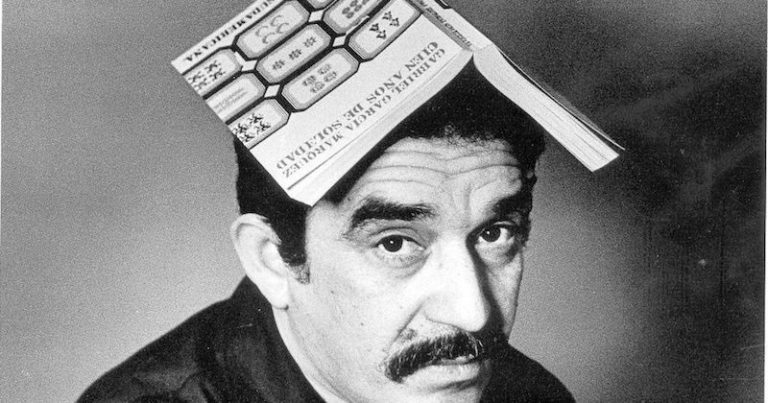

I remember the small, round tin lunchbox my mum packed for me with rice and chicken vibrating in my hands as we made the weekly drive in our clunky, baby blue Volvo, from Summer Hill to Hoxton Park to attend my abuela’s astrology lessons. Disguised by the dusty blonde brick exterior of the government housing block, her unit was legendary in my eyes, its interior decor evolving over months and years like a painter’s body of work. I later learned that these moods were often strategic and responsive to particular astrological transits—many years later she instructed me to wear uplifting red and dab rose oil on my wrists during a particularly damning Neptune transit.

As the upholstery, wall art, and rugs shifted according to color, some things were constants: the scattered semiprecious stones along the mirrored sidetable, the bookcase filled with astrology and crystal magic manuals and mythological texts, and the bowl of plastic fruit on the small dining table whose grapes I had, in earlier childhood, tried to chew more than once. On the balcony were plants surrounding a designated smoking wicker chair and often an audience of pigeons. Back inside, just past the balcony door, was a chunky beige PC running Windows 98 with a permanently magenta-tinted screen.

This day, the monitor threw blue-pink light over the mostly yellow-toned room, as the sun was setting and abuela was preparing to begin the lesson. She was reminiscent of a middle-aged Eartha Kitt, petite and expressive, but with an accent I have only heard on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. She passed out cue cards she had made to each of her students: three women ranging from their twenties to their fifties, and me, ten years old. There was a lilac card for each sign, with a short description, element, mode, ruling planet, and key phrase. I remember looking over Capricorn—my Sun sign—and finding the key phrase “I use.”

*

What does it mean to identify with astrology? Within astrological discourse, this question is usually a matter of the Sun, the luminary which determines our conscious self, our choices, our trajectory and life purpose. Mainstream predictive astrology and the rise of New Age countercultural beliefs in the 60s popularized the Sun sign as the most accessible and determining part of our chart. We don’t need to know the time of birth or even year to know our Sun sign (although more precise astrologers would challenge that). It is likely to be most people’s first glimpse of Western astrology.

But like the concept of identity itself, our Sun signs cannot encompass the whole of who we are. Astrological discourse has speculated on the prominence of Sun sign astrology in the West, in comparison to Vedic astrology which focuses more heavily on the Moon. The Sun may rule identity, but it also rules individualism and ego, and comes to strength in the signs Aries and Leo, traditionally associated with masculinity and action, pride, and self-orientation, all rewarded traits in patriarchal, colonial, neoliberal capitalism. In this same traditional astrological framework, the Sun is weakened in the signs Libra and Aquarius, which focus too heavily on relationships and communities respectively to have a strong self-concept.

As of yet, astrology has not manifested power structures along the lines of its signs. It is merely annoying to its detractors.

Stuart Hall, cultural studies theorist and exemplary Aquarius Sun, wrote about identity to unstick it from its false premise of stability. He forms a discursive approach which shows identity to be a process, often ambivalent and indeterminate, never fully “won” nor “lost,” neither “sustained” nor “abandoned.” Elaborated in his essay “Who Needs Identity?,” identity is thus often an urging toward stability, an investment in the “fantasy of incorporation,” which sometimes tries and always fails to erase internal difference. However, identities are also formed as a way to mark difference and exclusion, as they are “produced in specific and institutional sites within specific discursive formations and practices, by specific enunciative strategies.” Hall clarifies identity as bound to cultural meanings, formed by the interplay between political and historical context. Both unconscious and intentional, identity is more than an affiliation—it is a political project.

I sometimes try to imagine what Stuart Hall would say about a lot of things, astrology included, drawing on his warm yet incisive critical voice. Sun sign astrology is an essentialism, certainly. What does it mean to identity with an unchanging stock personality description, especially one often carelessly written to perpetuate assumptions about people’s motivations? Perhaps there is some agency in being able to choose to invest in stereotypes, even if, at the same time, believing in these simple stereotypes can close down and even damage the self. (Many, of course, resist overdetermination.) And perhaps it offers access to a rare sense of commonality for some, across hierarchies and more public, entrenched social identities.

Skeptics such as Benjamin Radford have compared astrology to racism due to this stereotypical, deterministic thinking, but these critics are usually unwilling to go beyond the realm of thought, and define racism as a purely interpersonal phenomenon, rather than composite matrices of domination that limit access and freedom. As of yet, astrology has not manifested power structures along the lines of its signs. It is merely annoying to its detractors. In contrast, many falsehoods lie within the stereotypical, deterministic thinking of patriarchy, white supremacy, anti-Blackness, transphobia, capitalism, ableism, homophobia—but these structural formations will never be considered irrational so long as they benefit those in power. The western notion of “rationality” is closer to a sense of legibility: what is able to be seen, measured, and understood within the frame of the West, and discrediting that which cannot be fully translated or captured.

Despite the one-dimensional astrology perpetuated by some critics, there are many shades of potential investment and basically no actual, enforced rules in astrology, making it one of the most unpredictable spiritual practices. No one will stop you from forming your own interpretations of planets and signs—although many astrologers will question you for attempting to include the recently discovered “thirteenth sign” Ophiuchus in your chart readings. Some astrological traditions have mathematical reasons for their interpretations of signs, planets, houses, limiting their scope to keep their charts in order. Others are more open to the expanse of different, fluid meanings and astronomical bodies. Some focus on fate and fortune, others on inner life and emotional growth, some on both.

Going beyond the simple Sun sign, there is the basic natal chart: constructed as a wheel divided into twelve sections, it paints a picture of the way the sky was oriented at the time of your birth. Knowing your birth time down to the minute can be crucial, and can mean the difference between a loud Leo Ascendant and a shy Virgo Ascendant. From there, the position of the twelve signs is set across the twelve houses, and the planets are scattered along the wheel accordingly. The planets are seen as points of “energy,” throwing emphasis to particular parts of your life. A planet’s sign determines its style of expression, and its house determines where its effects are most seen. From there, you can create charts for transits, solar and lunar progressions, solar returns, as well as synastry and composite charts mapping relationship dynamics, and draconic charts. Once you gain a feeling for the basic twelve points, you can then include different asteroids, fixed stars, or midpoints. The Sun sign is still incredibly meaningful, but as your knowledge expands, it becomes harder to see it as a defining personality trait. Past a certain threshold of knowledge, astrological charts become responsive and incomplete, reflective of the continual process of self-making.

*

My interest in astrology had a deeper foundation than Abuela’s lessons—it came with my kindergarten obsession with the anime series Sailor Moon. Each Sailor Senshi (then dubbed as “Scout”) had her own elemental kind of power, which I later learnt was somewhat cohesive with the astrological significance of her planet. I wanted to belong to space and to have my own special kind of power.

Sailor Moon creator Naoko Takeuchi’s celestial symbolism was fused with a mundane romanticism, directed towards friends and lovers alike. Relationships were held in equal weight to the quests and goals of the Sailor Senshi—often, the power of relationship was what fostered the strength to defeat the villain and restore peace. These emotional lessons imprinted on me as a lonely child, and turning to astrology seemed reasonable to figure out what my elemental power would (hypothetically) be.

Unfortunately there were no astrology books for children. I was contending with a 90s postfeminist boom in New Age self-help, which mostly encouraged Capricorn Sun women to exploit their canny investment skills and strategically date older men. I was left with a confused, premature self-knowledge of being serious, depressive, and achievement-oriented, which was probably lodged in my psyche for good. Capricorn is ruled by the planet Saturn, traditionally known as a “malefic” planet that brings suffering, and my early experiences with astrology were retrospectively colored by Saturn themes. It was embarrassing more than anything else, because at that time not many other people entertained astrology, kids and adults alike. But it was also painful in other ways, as I didn’t have the emotional toolkit to protect myself from being defined by astrologers whose interpretations often fed unhealthy notions of personality, selfhood and identity. My Capricornian “maturity” became a way to justify my isolation and distance from other children.

Neoliberal postfeminism tells you that you can do it all, you can find your inner power, and you have so much opportunity, so you have to make the most of it.

I only watched the first two seasons of Sailor Moon, the English dub broadcast on Cheez TV before school. Later series of Sailor Moon introduced Hotaru Tomoe, who transformed into Sailor Saturn. Her chronic illness and quiet demeanor hides her power to destroy and rebirth the universe. Takeuchi merged and blended some of the astrological themes of Saturn and Pluto in Sailor Saturn’s abilities, represented by the long scythe she carries: a symbol of harvest and the shift from spring–summer to autumn–winter, the conclusion of the agricultural lifecycle. In ancient astrology, Saturn was the farthest planet visible to the naked eye and thought to be the edge of the solar system, and thus was theorized as the planet ruling death, sickness, and loss. Ancient interpretations of a Capricorn Sun, being “born under the sign of Saturn,” were considerably harsher than the icy, reserved images fed to me from those astrology manuals for “the modern woman”—with exposure to this older mythos, I may have had a terrifyingly precocious understanding of myself as tethered to death. While relieved, I also mourn the baby goth that could have been.

Traditional astrology, derived from ancient astrology, focuses less on internal experience and traits and more on the events in an individual’s life, in line with its practice as divination. The Sun can indicate what your life path will look like, but can also be seen as a representation of your father, depending on the reading. Likewise, the Moon’s position can be used to divine health conditions, fertility, or events affecting your mother or even any significant women in your life.

The position of Saturn could show where your life’s difficulties lay so you could be reasonably prepared. Demetra George, an astrologer noted for her return to ancient Hellenistic astrology, makes a gentle case for good fortune/bad fortune astrology in , writing that:

. . . for many people, despite their best efforts and excellent aspirations, life continues to be filled with loneliness, unrealized potential, suffering, and failure. From an astrological perspective, the poor condition of certain planets in the chart can indicate that these individuals may have an extremely difficult time bringing about certain matters that will benefit them.

George suggests spiritual practice in the form of prayer and meditation, ceremonial rituals, and even modern psychotherapy as a potential remedy for people with afflicted charts. In her view, being carefully honest and upfront about weakness and bad luck in the chart is potentially compassionate, even just as a recognition that “bad things happen to people and [. . .] certain astrological factors can and do indicate these misfortunes.”

However, more modern astrology rejects this causal, fatalistic approach. The contemporary school of psychological astrology, based largely on Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, sees the chart as correlation not causation, reflecting meaningful coincidences which can be used to seek insight about the individual’s psychological experience, including needs, motivations, defenses and projections. Psychological astrologers such as Dane Rudhyar, Liz Greene, and Stephen Arroyo recuperated and rewrote astrological planets, signs, and houses as essentially neutral rather than conferring qualities of luck. A particular cornerstone of psychological astrology is Greene’s manual on Saturn, A New Look at an Old Devil, which conceptualized Saturn as able to provide valuable wisdom as part of experiencing hardship. My experience of Saturn transits have often been this kind of clarifying internal process where difficult situations teach me where my values and priorities lie. In line with the symbol of the scythe, Saturn transits can give you the opportunity to “reap what you sow,” where small advancements and long-term planning pay off.

In many ways, psychological astrology’s application is a form of emotional self-help, encouraging reflection and introspection, giving strategies for growth, and sometimes promising to be able to unlock inner power. Much is to be said about contemporary self-help, particularly in the neoliberal age, as it frequently promises happiness and fulfillment without questioning oppressive social structures, individualizing and depoliticizing mental distress and lack of fulfillment. Social work academic Joanne Baker’s research on young Australian women documents self-help and astrology as a particular “psychological strategy” for navigating neoliberal and postfeminist contradiction.

Neoliberal postfeminism tells you that you can do it all, you can find your inner power, and you have so much opportunity, so you have to make the most of it. Even if you’re struggling to pay rent, you’re still in underpaid casual work, you need a master’s now for the job you want, or your boyfriend won’t respect your boundaries, the solution is seeing how you are “attracting” these circumstances. The solution is “improving” yourself. The solution is “healing.” You have the agency to build a happy, fulfilling, successful life—you must remain optimistic.

Astrology is vague enough to carry both optimism and pessimism depending on emotional necessity.

The psychological strategies Baker details include general optimism, viewing difficulties as “learning experiences,” viewing others as “worse off,” and pragmatic fatalism. These all aim to obscure the patterns of exploitation and disadvantage present in these young women’s lives, as well as to avoid being labelled openly as “disadvantaged” or “oppressed” in any way. Baker notes that pragmatic fatalism—believing that certain things such as losing a job, an unplanned pregnancy, or other “failures” were predestined and meant to be—is incongruent with the general neoliberal self-belief that “anything is possible” if you work hard enough, try hard enough, etc. is belief in destiny and things being “meant to be” is possibly emotionally necessary for navigating current social structures, especially when pressured to reach a certain level of success. Totalized self-responsibility—if you fail, it’s entirely your fault—would be crushing, considering that failure is not something avoidable.

This pragmatic fatalism is omnipresent in astrology, even modern, psychological astrology. The question of why astrology has seen such a revival amongst millennials has been posed again and again, and I feel that this is part of the answer: astrology is vague enough to carry both optimism and pessimism depending on emotional necessity. Look to contemporary psychological astrology to unlock your future and become a better you, and look to traditional astrology to process your past and radically accept what is. This is an oversimplified binary, of course, and I don’t believe most people approach astrology in such a purely pragmatic way.

I believe sometimes—even if you’re half aware you’re looking up your transits because you’ve been crying for three hours and it’s 4am and you need something to calm yourself down because you have a doctor’s appointment you can’t miss at 11am the next day and you’ve been sleeping in too much and mornings are supposed to be the most productive time of the day and anxious thoughts keep rattling through your brain—a little bit of the magic can filter in, like a slight breeze, when you check your astrology app and see that Jupiter has just moved into Sagittarius, a traditionally lucky and benevolent placement. In that moment, things feel a bit more in place, and I half-know it’s not true, but my heart has slowed down, because I’ve remembered that both the planets and my feelings keep moving.

Progressing through her interviews with young Australian women, Baker comes across an “atypical case” of a woman who does not attribute difficult experiences as “learning experiences.” Having been the victim of sexual abuse and violence, and currently living in poverty as a single mother of two at the age of 24, she made little “optimistic revisions” to her life narrative, instead of openly expressing regret and emotional distress from her experiences. Notably, however, she was also the only woman interviewed by Baker to voice empathy for others who shared her experiences, and to challenge the status quo by asserting that women deserved more.

Overall, those women who denied their own difficulties also tended to close down the possibility of fully recognizing the difficulties of others, and were less likely to draw connections between them. Their belief in meritocracy and denial of victimhood—being subjected to by forces outside of their control—was also projected onto those seen to be perpetual “failures” in the eyes of neoliberal capitalism: unemployed people, young single mothers, migrants, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people with disabilities and chronic illnesses. A lack of self-compassion translated directly to reduced compassion for others, which Baker acknowledges is “likely to reduce the possibilities of mobilization for social change.”

Using astrology to navigate and survive neoliberal capitalism, patriarchy, racism, oppression generally carries the risk of falling into blaming people for their circumstances, so long as it draws on the heightened personal responsibility pushed onto individuals to “make their own destiny.” Although I have no experience in any other spiritual practice, I’m aware that transcendence is part of the appeal, believing that one can go beyond what is handed to you, that you can truly become “bigger than your circumstances” given the right touch of fate and faith. There’s something else on your side, whether that be planets, archetypes, spirits, ancestors, powers much older than these destructive systems we’re entangled in, even as we speak it through the languages and histories of those systems.

Using astrology to navigate and survive neoliberal capitalism, patriarchy, racism, oppression generally carries the risk of falling into blaming people for their circumstances.

Love possibly falls under this category, as a very, very old power. In Sailor Moon, Usagi Tsukino’s elemental power is seemingly “love” or “healing,” sending vibrant, crushing pink hearts out of scepters and wands. It corresponds with the Moon’s astrological association with the emotional body, physiological response, maternity, attachment bonds, lineage and kinship. Self-healing and healing others is on the same continuum, in which connection can be found in being able to admit one’s vulnerabilities and thus recognize the vulnerabilities of others. Joanne Baker’s “atypical case” reminds me of Sara Ahmed’s writing on fragility, in which she resists the temptation of aspiring to wholeness, and instead encourages and embraces a sense of brokenness—from emotional, political, collective pain and vulnerability—in order to fully see and connect with the brokenness of others.

*

If I could go back in time, I might not have invested in learning about astrology so early that I became so unthinkingly invested. I understand why some people advocate for children to grow up without religion. My brain was too young and pliable, too hungry to make sense of other people.

Growing up with religion often seems to come with community, rituals, places of worship, all embedded in cultural practice and significance. My only sense of what church could be like came from Abuela, both in the way that she could hand down transcendental wisdom and guidance as casually as she would pour my sister and me glasses of juice in the morning, and in the sanctuary and protection her space gave me. I was not only a Capricorn, but a racially confused and isolated Afro-Nicaraguan girl growing up in predominantly non-Black spaces. Abuela’s unapologetic vibrancy drew me in. Her astrological practice seemed inextricable from the glow she put out. It was one of the few models I had of Black womanhood, and one that seemed to recognize how futile it was to try to assimilate.

I consult her on occasion and she sends me links about important transits on WhatsApp, but ultimately we have our own individual ways of practicing astrology. Visiting her a few years ago in Cairns—she refuses to move back to Sydney because it’s too cold for her—we spent quiet mornings on our laptops with cups of black coffee. The solitary nature of practice made astrology feel like witchcraft more than any association with the occult. While I never thought I would be totally ostracized for my belief in astrology, I also knew my interest was something not many other people would take seriously.

I realized that it was possible to engage in astrology without necessarily fusing it to the core of your being—it could be light and fun.

Years later, watching astrology become more popular online—particularly on Tumblr, Twitter and Instagram—was dumbfounding at first. It was not something I ever expected, although I did notice that for a few years before that, people began engage me in conversation about astrology as an enjoyable topic rather than as an absurdity. I even started to find people whose level of interest met mine—they knew their whole charts, and tracked their transits—and a part of me began to relax about it. It felt warm to be understood.

Even then, a lot of the astrology I saw was a blend of meaningful self-reflection and memes. The quantity of memes and relatable posts began to rise and rise, and even seasoned astrologers began to make their own, using the reaction image of the moment. I realized that it was possible to engage in astrology without necessarily fusing it to the core of your being—it could be light and fun. The sheer volume of memes led to its own complexity of meaning, often reflecting the creator’s personal experiences with other people, coded by their own individual signs.

I think this kind of simple, joyful engagement, while reliant on astrological stereotypes, isn’t quite equivalent to the typical, reductive Sun sign astrology of decades past. The messy sprawl of diverse astrological content is one reason, but another is the general lack of interest in proving astrology to be real or justifying its practice. There’s less of an investment in being totally “rational” or “logical.” It operates on the same level as having lucky omens, soulmates, believing in ghost stories—concepts which aren’t fully filled out, stable or coherent, leading them to fluctuate in significance. These things can feel so real, even as you know your understanding is piecemeal. It affects us as a twinge or a jolt, or a shiver. It disjoints from the framework of “rational” existence, both as emotional epiphany and silly tweet.

*

Traditional Western astrological texts refer to the fire and air signs as having a “positive” charge, being extroverted and focused outwards, being dynamic and creative (fire) or objective and communicative (air). Earth and water signs occupy the introverted, “negative” binary opposite, associated with embodiment and materiality (earth) and emotionality and connection (water). In the book Symbols for Women: A Feminist Guide to the Zodiac, Sheila Farrant critiques this gendered framing of the signs, instead constructing a “matrilineal zodiac” based on different female mythological figures. She even invokes the writer Simone Weil as a figure for Aquarian women.

As an astrologer and gender studies major, finding Symbols for Women at a university book fair was astounding. Farrant shifted the valence of each element, showing how each could be interpreted in a masculine or feminine way, and further, how patriarchal ideology underpinned our understandings of personality and psychology itself. In deconstructing the hierarchical binaries present in astrology, where body/emotion is implied to be of a “lower order” than mind/reason, Farrant radically opens up the zodiac. She also makes note of how each sign operates “under patriarchy,” acknowledging that social structure constrains personal expression and personality through upholding specific values.

While psychological astrology can present seemingly limitless opportunities for growth, and traditional astrology preordains fortune, Farrant’s feminist astrology conceives of energies and archetypes which are stifled by an imbalanced social order. One example is her interpretation of Pisces, often stereotyped as overemotional, reclusive and with addictive, self-sabotaging tendencies. Farrant returns to the core themes of Pisces: responsiveness, vulnerability, global interconnection, dreams and the subconscious, creativity. Instead of essentializing people with Pisces aspects as “just being that way,” she speculates that existing in Eurowestern capitalist modernity as a Pisces is incredibly difficult—Piscean values are not respected or integrated into wider society, hence the escapism and need for sanctuary.

Like many other disciplines, most of the historically prominent astrologers were men, but the most recent wave of interest in astrology is led by women and LGBTQI+ people. Queer astrology has emerged as a specific practice, with astrologers like Chani Nicholas and Alice Sparkly Kat synthesizing politics and astrology, encouraging movement towards liberation. Astrolocherry, a renowned, poetic Tumblr astrologer, also strongly hints that outer planet transits (Uranus, Neptune and Pluto) are on the side of the oppressed, bringing greater social structures closer to dissolution.

These astrologers use a combination of serious, thoughtful analysis with tongue-in-cheek memes to communicate to their audiences, shifting between different registers to display the full range of astrological practice. Relatable symbolism is at the heart of astrology, forming multiple levels of connection, none requiring commitment. As Chani says at the beginning of her new moon workshops, “take what you need.”

*

Seeing psychics and astrologers advertise the ability to know events in your future, detect unfaithful partners, find true life purposes is stressful to me. A fortune teller once walked into the florist shop I used to work in, during an idle afternoon. I told him I wasn’t interested (knowing my natal, draconic and progressed chart is already too much) but he was generous enough to say he sensed success from me.

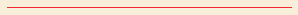

Wildfire in Yosemite National Park, 2009, by Kip Evans.

Wildfire in Yosemite National Park, 2009, by Kip Evans. Sundarbans National Park.

Sundarbans National Park.