Everything you know about Anton Chekhov is wrong.

Chekhov the downcast tubercular writing magnificently mournful plays about the declining aristocracy on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution, the king of the country whose national anthem is the minute-long sigh. The picture lasts because it’s what we want from our 19th-century Russians: gravity, fatalism, melancholy, minds wracked by the Big Questions. We wouldn’t want this kind of writing today—too un-ironic, too free with emotion, too un-relativist, too naive in thinking that the Big Questions have resolution at all. But we love the echo.

This isn’t the person I think of when I think of Chekhov. I think of an 1890 photograph of a 30-year-old man returning by steamer from Asia. He’s no rake on a grand tour—he’s just completed a journey that would be arduous even today: a humanitarian visit to a penal colony in the Russian Far East. But neither is he a brow-furrowed Marxist scribbling a manifesto as his train races back to the capital. No, he has taken the long way home: Hong Kong, Singapore, and Sri Lanka, about which he has written, to a patron and friend, “When I have children, I’ll say to them, not without pride: ‘Hey, you sons of bitches, in my day I had sexual relations with a black-eyed Hindu girl, and you know where? In a coconut grove on a moonlit night. . . . ’”

This isn’t a sodden aberration when no one is looking. Mr. Chekhov likes his ladies—his Lydias—of the capital; sometimes he goes out with Lydia Yavorskaya, and sometimes Lydia Avilova.[1] And he’s no urban snob. At a rural wedding at which he served as best man, as he wrote to his sister Maria, he “saw a lot of wealthy marriageable girls . . . but I was so drunk the whole time that I took bottles for girls and girls for bottles! One of them . . . kept striking me on the hand with her fan and saying, ‘Oh, you naughty man!’”[2]

In the 1890 photo, the sun seems high, and Chekhov takes shelter on a bench alongside an acquaintance. Each is cradling a mongoose—why not. Chekhov is dressed like a cross between a peasant, an Eastern guru, and a rake: A fedora high on his forehead, an open-necked shirt, loose white pants. He’s grinning like a man who’s just risen from a choice bed, his hair mussed and his rumpled goatee clearly Leonardo di Caprio’s secret inspiration all these years. He is the very picture of joy and vitality.

Chekhov was moved by great passions—I can’t think of a Russian great with more skin in the game. But just as few could be as funny or bawdy amidst the sobriety because . . . well, because that’s how life is.[3] Forget that, early on, Chekhov made his living through humor pieces, a Dickens-in-reverse who got paid only if he came in under 100 lines. (He was paying for his medical education then, the “wife” to which literature was a “mistress.” Not for long.) I’m talking about “The Siren,” a lip-licking ode to food in the Russian mouth that reads like an extended version of that Gogol exultation about Ukrainian dumplings in sour cream flying into a certain gentleman’s mouth by themselves.[4] I’m talking about the wry, playful humor that breaks through the foliage of even the darkest story: “Hundreds of miles of deserted, monotonous, scorched steppe cannot produce such gloom as one man when he sits and talks and nobody knows when he will leave,” he writes in “An Artist’s Story,” otherwise an account, included in this collection, of multiple sorrows. Or take the second epigraph of this essay. Take any “dark” story and count the exclamation marks.

Nabokov came from the library. Gogol from the government office. Dostoevsky and Tolstoy from the clouds, where they wrote books meant to deluge the ground and sweep away the old order, ushering in a utopia of Christian suffering and redemption, in the former’s case, and moral rectitude, rural life, and vegetarianism, in the latter’s. Chekhov came from the earth. Literally. He was the only great Russian writer of the 19th century born to the peasantry rather than the nobility, the reason why the peasants in his stories are complex human beings, neither saints nor sinners, and as understandable as they are sometimes degenerate, rather than pegs in grand philosophies.

“While Tolstoy and Dostoevsky both believed that Christian faith was the main source of moral strength for the impoverished and ignorant Russian peasants,” the Chekhov scholar Simon Karlinsky has written, “Chekhov’s much more closely observed and genuinely experienced picture of peasant life shows nothing of the sort.” Just read “In the Ravine.” After the funeral for a defenseless creature gruesomely murdered out of greed and spite by an extended family member, a funeral during which “the guests and the priests ate . . . with such greed that one might have thought that they had not tasted food for a long time,” listen to “the priest, lifting his fork on which there was a salted mushroom,” offer to the creature’s meek and suffering mother this magnanimous comfort: “Don’t grieve . . . For such is the Kingdom of Heaven.” One imagines that just then the salted mushroom meant far more to him. As Chekhov wrote in a letter, “I have peasant blood flowing in my veins, and I’m not the one to be impressed with peasant virtues . . . Tolstoy’s moral philosophy has ceased to move me . . . Prudence and justice tell me there is more love for mankind in electricity and steam than in chastity and abstention from meat.”

“Chekhov came from the earth. Literally. He was the only great Russian writer of the 19th century born to the peasantry rather than the nobility.”But it’s also in Chekhov that you find the opposite portrait of a religious man. (Consider “The Letter,” included in this volume.) “For all their preoccupation with religion,” Karlinsky writes, “[Tolstoy and Dostoevsky] never thought of making an Orthodox priest, deacon or monk a central character in a work of fiction as Chekhov did . . . Most of these men of the Church are presented as full-blooded human beings with their own joys and problems.”

As radical as it is simple: Tell things how they are, not how they should be. This approach is as natural today as it was radical a century ago, and every time art moved from a depiction of the idealized to the real. (Think of European painting going, in the 17th century, from “angels with gauzy wings” to “the actual look and feel of a world, which, after all, God has created,” as the art critic Robert Hughes has put it.) If Dostoevsky was concerned by humanity in extremis, if Tolstoy sought final, unvarying answers, Chekhov concerned himself with ordinary people, and felt that no single philosophy could answer for a world of perennially shifting circumstances, to say nothing of the fungibility of human nature—the view of an empiricist and clinician, as per his training. He went quietly about the same work the others went about loudly.

As Dr. Zhivago says in the famous novel, Chekhov’s work has a “modest reticence in such high-sounding matters as the ultimate purpose of mankind or its salvation. It’s not that he didn’t think of such matters . . . but to talk about such things seemed . . . pretentious, presumptuous.” It was a matter of creative philosophy: “I think that it is not for writers to solve such questions as the existence of God, pessimism, etc.,” Chekhov wrote in another diamond of craft advice. “The writer’s function is only to describe by whom, how, and under what conditions the questions of God and pessimism were discussed.”

But temperament played a part, too; it won’t come as a surprise that Chekhov had no great notions of himself. “If I have a gift that should be respected,” he wrote to an older novelist who had written to urge him to take on a novel, “I had got used to thinking it insignificant.” Some of this had to do with his beginnings: No one has diagnosed as articulately the self-abnegating servility which the low-born of the time and the place—the serfs, Russia’s version of the feudally bonded, and their descendants—carried within them.[5] “Try writing a story about how a young man, the son of a serf . . . brought up venerating rank, kissing the hands of priests, worshiping the ideas of others, thankful for every crust of bread . . . hypocritical towards God and man with no cause beyond an awareness of his own insignificance—write about how this young man squeezes the slave out of himself drop by drop.” Chekhov managed to do just that, a course of rigorous self-education and -improvement despite low means and a petty tyrant of a father that accomplished, in the elegantly acidic formulation of Chekhov scholar Aileen Kelly, “what Tolstoy spent his life trying vainly to do: He reinvented himself as a person of moral integrity, free from the disfigurements inflicted by the despotism that pervaded Russian life.”

If Chekhov took his talent lightly, he altogether ignored his health. He had tuberculosis for a decade before he finally bothered to have it diagnosed, so busy was he with writing and the social-improvement projects to which he constantly devoted himself. He spent the winter of 1891-92 working to relieve a countrywide famine caused by the previous summer’s failed harvest, “concentrating, with characteristic practicality, not on charity handouts, but on an organized campaign to prevent the peasants from slaughtering their horses for food, a practice that perpetuated the famine cycle, since it left no horses for next year’s spring plowing” (Karlinsky). The following summer, a cholera epidemic broke out in the area several hours outside Moscow where Chekhov had just purchased a home; he spent the next two seasons in an unpaid position battling the epidemic, and treating a thousand peasants along the way.

Every community he encountered was left the better for it: The library in Taganrog, in southern Russia, where Chekhov was born, was the beneficiary of a lifetime’s steady supply of books in multiple languages, as were libraries near his country home and in Siberia. He built schools, arranged for the construction of a local highway, created a clinic for alcoholics, bought horses for peasants who needed them, fund-raised for a journal of surgery, and even helped set up a marine-biology laboratory. Pleaded with to relent, he said he was happier giving medical care to peasants than enduring the literary chatter in Moscow.

Even on his deathbed, he couldn’t bear to turn away all those who crowded his doorstep. Maxim Gorky, one of the many writers who benefited from Chekhov’s encouragement and intervention, put it well: “In the presence of Anton Pavlovich everyone felt an unconscious desire to be simpler, more truthful, more himself, and I had many opportunities of observing how people threw off their attire of grand bookish phrases, fashionable expressions, and all the rest of the cheap trifles with which Russians, in their anxiety to appear Europeans, adorn themselves, as savages deck themselves with shells and fishes’ teeth.” A single sentence of Chekhov’s, after Tolstoy visited him at his rural clinic, says it all: “We had an extremely interesting conversation, extremely interesting for me because I listened more than I spoke.”[6]

Chekhov brought the same values to his craft and his politics, though here they were far less welcome. The craft moves pioneered by Chekhov are de rigueur in high-end literary fiction today, but they were heretical in their time. Chekhov’s stories are “all middle like a tortoise,” John Galsworthy is supposed to have said; many have referred to Chekhov’s “zero ending.” It’s true that he can spend two-thirds of a story winding up, with conventional plot an afterthought left for the craft manuals. But if you ease into it, if you suspend the expectation of dramatic convention that is the norm even today, you will find yourself transported by description and characterization—of people, of places, of the human condition—as close as anything Flaubert observed about his clerk in felt slippers, and perhaps unmatched in its alchemy of sensitivity, wisdom, precision, and verve. Also the miracle of its simultaneous soulfulness and lack of adornment.

Look at the descriptions lavished on the secondary characters as “The Privy Councillor” winds up (“Spiridon measured him several times, walking round him . . . like a lovesick dove round its mate”), the description of winter that opens “An Attack of Nerves,” the casually aphoristic pronouncements that litter every story (“Learned things ruin the appetite,” in “The Siren”). He says in a line what would take another a paragraph: “I am old and not fit for struggle; I am not even capable of hatred” (“Gooseberries”). “Chekhov’s language is as precise as ‘Hello!’ and as simple as ‘Give me a glass of tea’,” the early Soviet poet Mayakovsky wrote. (And here was a man in search of revolutionary forms for a new nation.) “In his method of expressing the idea of a compact little story, the urgent cry of the future is felt: ‘Economy!’”

“He built schools, arranged for the construction of a local highway, created a clinic for alcoholics, bought horses for peasants who needed them, fund-raised for a journal of surgery, and even helped set up a marine-biology laboratory.”But no Chekhov reader has to subsist on high aesthetics alone. On so many occasions, the situation the author has been laying out for us suddenly coheres into something devastating and whole, the story snaps straight as a sail in high wind, and one begins to read feverishly. See if you can pinpoint the moment, in “The Privy Councillor,” “The Artist’s Story,” “The Name Day Party,” “In the Ravine.” Far less Chekhov ends at “zero”—in other words, no differently than where it started—than the stereotype has it, but there was philosophy behind the stories that do. Sometimes things change, sometimes not, non? Sometimes the sinner repents (Crime and Punishment), sometimes she goes unpunished (“In the Ravine.”) Sometimes, the adulterers go for it (and pay for it, as in Anna Karenina), but sometimes they don’t (and are no happier for their restraint). Read a story like “About Love” and tell me that it ends at is “zero,” even though, technically, “nothing happens.” To my mind, it’s a more moving exploration of love than the famous “The Lady with the Pet Dog,” where something certainly does.

For all its flickering beauty, real life offers little moral justice or dramatic convention. Take the moment, in “The Lady with the Pet Dog,” after the adulterers, Gurov and Anna Sergeyevna, have slept together for the first time. Anticipation has given way to post-coital gloom. “Her features drooped and faded, and her long hair hung down sadly,” Chekhov writes of Anna. “‘It’s not right,’” she tells Gurov. “‘You don’t respect me now.’” The story, imagined conventionally, seems to beg for anything other than what follows: “There was a watermelon on the table. Gurov cut himself a slice and began eating it without haste. They were silent for at least half an hour.” Gurov doesn’t do this because he’s unfeeling, but because it’s the at once unexpected and inevitable thing that a person finds himself doing in such a circumstance, like plosive newlywed kisses sending up calf spasms and a taste of over-sweet raisins.

This is not the way Dostoevsky and Tolstoy wrote, which is, perhaps, the reason we wouldn’t call either a modern writer or, for that matter, a direct influence on much of posterity, geniuses though they were. Some of the most progressive literature of the last century—from Russia’s Silver Age surrealists to Western Europe’s modernists to Flannery O’Connor’s flaying precision (if not Chekhov’s tenderness) to W. G. Sebald’s anti-narrative instinct—has Chekhov’s mark on it. It’s no accident that Alice Munro, the Canadian short-story master and recent Nobel Prize winner, is often called “our Chekhov.” From the portraiture so close, at once full of precision and sweep, that makes you forget you’ve read 20 pages and the story hasn’t “started”; to all that set-up suddenly shaping into a predicament that puts your heart in a vise; to the way both situate so many stories inside stories told by others: it’s Chekhov.

It won’t surprise you to learn that Chekhov also declined to inhabit the straitjacket for which every Russian writer of the late 19th century was expected to fit himself by the literary establishment: that of the liberal critic of autocracy. It isn’t that Chekhov didn’t agree with the politics; he objected to the lack of freedom in the establishment’s dictates on how freedom should be promoted. He was against falsehood, hypocrisy, and compulsion in all corners, and didn’t hesitate to disagree with “his own” (just re-read the first epigraph of this essay). He had friends on both sides of the aisle, and in a poignantly naive view, as relevant for America today as for Russia then, “it [did] not even occur to him that unbiased observations . . . might be incompatible with patriotism” (Karlinsky). In staid times, such a man feels like a seer. In divided times, like a miracle. You want to live in his country, except it has so few citizens.

Chekhov was savaged for his supposed lack of ideology. Usually, it didn’t get to him: he nominated an especially scathing critic of his work to the Russian Imperial Academy. But sometimes it did. (He was no wallflower.) “You once told me,” he wrote to another author, “that my stories lack an element of protest, that they have neither sympathies nor antipathies. But doesn’t the story protest against lying from start to finish? Isn’t that an ideology?” (Pity the author in a politicized society in a polarized time. Lampedusa, who portrayed Italy’s old, pre-Republican guard with nuance and empathy, and who himself, in the words of his biographer, “remained too skeptical and disillusioned to be a genuine democrat or a liberal,” was excoriated by the Marxists who dominated Italian literary criticism after the war.) As Nabokov wrote, “Chekhov’s genius almost involuntarily disclosed more of the blackest realities of hungry, puzzled, servile, angry peasant Russia than a multitude of other writers, such as Gorki for instance, who flaunted their social ideas in a procession of painted dummies. I shall go further, and say that that the person who prefers Dostoevski or Gorki to Chekhov will never be able to grasp the essentials of Russian literature and Russian life.”

A doctor committed to observable reality rather than ethical or dramatic convention, Chekhov also wrote about sex as a physical phenomenon rather than a moral dubiety best seen through Victorian gauze. (This didn’t endear him to Tolstoy, either.) Radically, he wrote about the predicaments faced by women with the clarity of a non-ideological feminist. (By non-ideological, I mean that he saw those women as clearly as he saw their oppressors.) He got married, at 39, to Olga Knipper, an actress who spent most of her time in Moscow and St. Petersburg while he remained in southern Russia for his health, an arrangement so unusual for its time (though not for ours) that even Chekhov’s most intelligent critics have been unable to refrain from seeing it as “pathetic” and “unhappy.” But if you read Chekhov’s letters, you’ll see that the terms not only suited him—he agreed to marriage for Olga’s sake—but made him rather frisky. (He called her “doggie.”) A man of the earth to the finish, he even wrote about ecological ruin, a subject that has trouble getting traction even today. He was 19th-century Russia’s greatest modern.

*

I used to feel little for Chekhov. I was born in the Soviet Union and majored in Russian literature at university to try to reconnect with my heritage after a decade of trying hard to pass for American. I was riven with confusion and doubt—so is every undergraduate, but I had an extra piece due to losing my home country at nine—and was easily seduced by the grandeur, nobility, moral preoccupation, and clarity of the grandees we read. America felt free, but more frivolous, than the Soviet Union. Here was the opposite of frivolity. Here were writers who believed—no, took for granted—that the writer was a moral accountant to a fallen world, charged with showing the way forward. (And that there was a way forward, as opposed to an endless array of equally compromised truths.) From a young age, my parents had generously exercised in me a self-respect, not to say self-regard, that few children get to feel. That ego was trampled by immigration. In America, I felt inept and painfully out of place. Tolstoy, Dostoevsky—even the hand-wringing Turgenev—helped me find value, dignity, purpose.

It would take nearly 20 years to begin to see the occasional falsehood in the neat tie-ups of traditional storytelling, or in the protagonist breaking through to some understanding at the end of the story—to see that writing this way often has as much to do with the author’s needs as with those of his characters. In my early years here, I craved only one thing: certainties. I cycled through many false ones before Chekhov put me at rest about their impossibility even for less bifurcated people. If you can hold on to that, he seemed to be saying, you might live in a little more peace and write in a little more truth.

*

Perhaps the saddest way in which Chekhov remains relevant for our times is how accurate, in spirit, his portrait of Russia remains: power without account; greed, nepotism, and boot-licking; stability at the expense of freedom. What would Chekhov say of Vladimir Putin? He wouldn’t say anything about Putin. He might write a story about Putin’s press secretary misplacing the cufflinks the President gave him, which sends him into such a frenzy that he commits a crime so the most noticeable thing about his wrists is the handcuffs around them. Except that law enforcement doesn’t dare touch the President’s circle, and the poor man remains free, his torment in full view. (It would be called: “Cufflinks.” Or: “The Press Secretary.”) Or, less pointedly, the story of a Moscow man with a long walk home from the metro station, long and deflating, until he steps into a grocery and, somehow—well, out of desperation; to feel alive, perhaps—manages a flirtation with the counterwoman that leads to a relationship. Only there is enough initiative in him only for that gesture, and little by little the initiative in the family must migrate to the woman. Only that she does not want the initiative. She wants to be looked after. But they don’t divorce. They keep going, partly from fear, partly from suspicion that the human spirit has enough grace in it that there is still kindredness for them to discover. And enough mystery that we never know when we’ll manage to rise above ourselves once again.

And what would Chekhov say of America today, and America of him? Would it revere him as much as it reveres the playwright-of-twilight hologram, or would his actual perspective prove a little too sandpapery? For he would savage, equally, the witch-hunts enacted by social justice warriors, the soul-sellers lining up to lie for Trump, the provincialism of liberal echo chambers like New York and San Francisco, and the media’s reductions and manipulations. He wouldn’t touch the actual headlines, of course—he would write about individuals in concrete situations—but his brief would be the same: human nature, and its tendency equally to confusion and clarity; to small-mindedness, greed, and vulgarity as much as to generosity, self-transcendence, and love, all heavily dependent on circumstance. His stories highlight this above all, usually without judgment, always without bombast and remedy. How did such a “quiet man” and non-ideologue manage to survive such an unquiet, ideological century?

*

[1] Naturally, the latter used the acquaintance to press a manuscript on the author. “When you describe the miserable and unfortunate, and want to make the reader feel pity,” he responded, “try to be somewhat colder—that seems to give a kind of background to another’s grief, against which it stands out more clearly. Whereas in your story, the characters cry and sigh.” This advice wouldn’t be out of place in an MFA program today.

[2] The entire time, he adds, “her face wore an expression of fear.” He goes on to report that the newlyweds “kissed so vehemently that every time their lips made an explosive noise… I had a taste of oversweet raisins in my mouth, and got a spasm in my left calf.” In its precise and contradictory observations, the acute perceptiveness of its ostensibly illogical associations, the way its humor lives alongside something darker, the letter is a Chekhov story in miniature.

[3] As Nabokov—no great mug in life and, if a wit on the page, then a heatless one—wrote, “Chekhov’s books are sad books for humorous people; that is, only a reader with a sense of humor can really appreciate their sadness… Things for him were funny and sad at the same time, but you would not see their sadness if you did not see their fun.”

[4] This kind of antic epicureanism, so readily associated with Gogol, has as much to do with the man—a megalomaniacal, hypochondriac priss and sexual paralytic—as the gloom-and-doom angle does with Chekhov.

[5] I shiver every time I read what Denis Grigoryev, “a puny little peasant, exceedingly skinny, wearing patched trousers and a shirt made of ticking,” says to the magistrate investigating him for a minor infraction in the story “The Culprit”: “That’s what you’re educated for, our protectors—to understand. The Lord knew to whom to give understanding.”

[6] Is there a greater pair of frenemies in literary history? Tolstoy had been mortified by Chekhov’s perspective on the peasantry, but, according to Gorky, he had “tears in his eyes” over the saintly heroine of Chekhov’s “The Darling,” included in this volume, the story of a woman who assumes the views of the men with whom she takes up. Too bad Chekhov meant that this made her pathetic. And he came to revile Tolstoy’s anti-sex manifesto “The Kreutzer Sonata”: “To hell with the philosophy of the great men of this world! All great wise men are as despotic as generals… because they are confident of their impunity. Diogenes spat in people’s beards knowing that he would not be called to account; Tolstoy calls doctors scoundrels and flaunts his ignorance of important [medical] issues because he is another Diogenes whom no one will report to the police or denounce in the papers.” But Chekhov venerated Anna Karenina because, he felt, it ideally formulated a problem it did not try to resolve, Chekhov’s measure for true fiction. That didn’t stop Chekhov, of course, from “rewriting” its plot in at least half-dozen short stories, three of which—“About Love,” “Anna on the Neck,” “The Darling”—are included in this collection, all of them implicit rebukes to Tolstoy’s quite undeniable resolution of Anna’s problem: The adulterous shall be smitten. And yet, it was typical of Chekhov that, for all their disagreements, the men maintained a warm, cordial relationship.

__________________________________

From the introduction to Chekhov: Stories of Our Time, trans. Constance Garnett, Ilan Stavans, and Alexander Gurvets. Used with permission of Restless Books. Introduction copyright © 2018 by Boris Fishman.

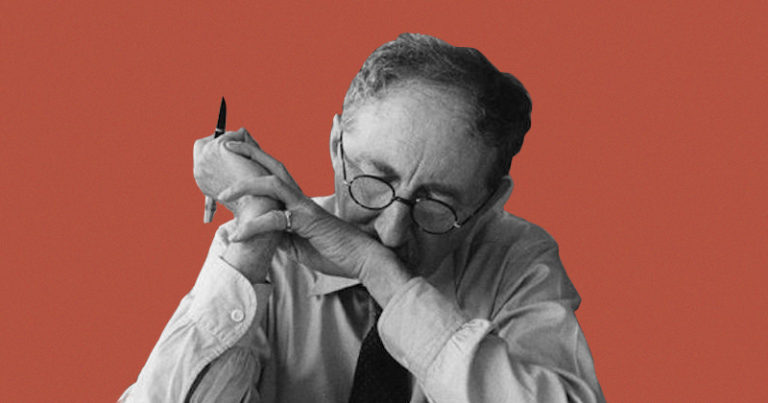

Kenneth Grahame at 30: a rising young banker, and at the same time one of

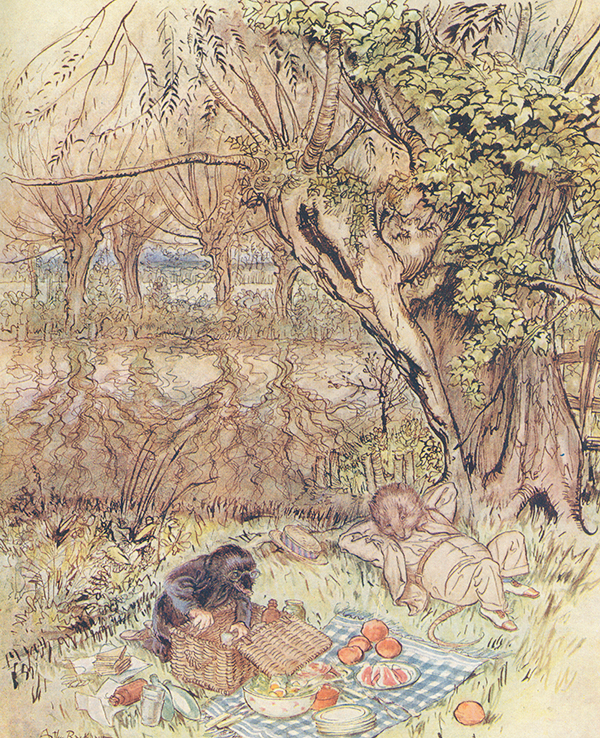

Kenneth Grahame at 30: a rising young banker, and at the same time one of “There’s cold chicken . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscress

“There’s cold chicken . . . coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickledgherkinssaladfrenchrollscress

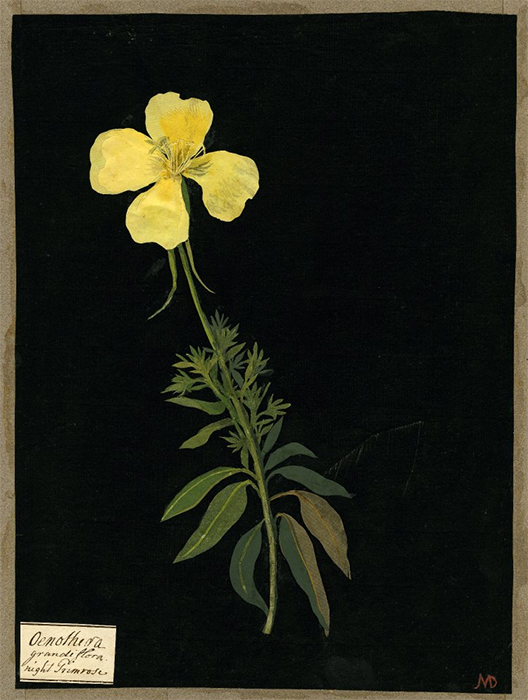

Mary Delany, Night Primrose, 1780. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Mary Delany, Night Primrose, 1780. © The Trustees of the British Museum.